How to Unlock Foreign Languages: 11 Principles

From November 2013 — March 2014 I worked remotely and traveled in South America. Working remotely and exploring the world is something I’ve wanted to do ever since I first learned the term “location independent” as a college sophomore. But until this trip, I’d never done it. So with no lead time, in early November I booked a one-way ticket to Buenos Aires.

Just one problem: I didn’t speak Spanish. I took Spanish in high school, but I couldn’t remember anything useful. And I’m not sure I could apply it in conversation even if I could remember it.

Onboard the redeye flight from Miami to Buenos Aires, my lack of Spanish was immediately clear. I sat next to an Argentine man who turned to me and started speaking. Even though he spoke simply, I could not understand him. It had already been an eighteen hour day, and my best intentions failed within ten seconds. Flush with embarrassment, I admitted defeat: “no hablo español.”

Fast-forward six weeks to arrive at one of the proudest moments of the trip: I sitting in a dark little cerveceria named Konna in Bariloche, in Northern Patagonia, drinking beer surrounded by native Spanish speakers. And having real conversations in Spanish. Conversations that went beyond what foods I had eaten, what I thought of the town, and where I was traveling from and to. A real conversation amongst friends in a bar, for 2 hours.

This was what I’d been working my ass off for. The crowning point of the night when one of the women at the table, my lovely Spanish teacher Mariela, said that my progress amazed her. After a comment about my love of mate, steak, and naps, she declared that I was Argentino Argentino. I beamed like a kid with his first trophy.

I wasn’t fluent and my Spanish wasn’t perfect, but that wasn’t the point: I was having a blast, actually speaking real Spanish with real Spanish speakers in a real conversation. That is the point: the cultural experience and growth.

So how did a gringo like me go from “no hablo” to “Argentino Argentino”? That’s what this post is all about: my first attempt at hacking language learning, the approach I took, and the lessons. I’ve taught this approach to about twenty other people who have all been able to speed up their progress. While this is a developing process, it’s one that works.

Before we dive into the nuts and bolts of this process, we need to discuss a few assumptions and the mentality of the learner here.

Assumptions

First of all, I assume you have your own reasons for wanting to learn another language. It doesn’t matter what that reason is, but you do need your own. If you need convincing that learning another language worth your time, or you think that your native culture/language is superior to others, this is not the post for you.

This is from the perspective of a native English speaker, and it’s intended for an audience of other native English speakers. That said, as far as I can determine the principles in this process apply for any native to target language pairing.

I assume your goal is to use the language as native speakers do, and that you care about conversation and spoken interaction more than writing. This is opposite the approach most people have in school, which focuses on grammar and written work. We’ll do that too, but not until much later.

Finally, I assume you will dedicate time every day to the language learning practice. Thirty minutes a day will yield steady progress, but increasing the amount of time will definitely speed up your progress. But daily practice is essential if you want fast progress.

Mentality

What’s on the line? By when?

Starting off with the right mentality is critical to having a positive experience with a new language. Having a goal — ideally, with a deadline and/or some sort of stakes, such as a bet — will help you keep moving on days where you’re feeling sluggish.

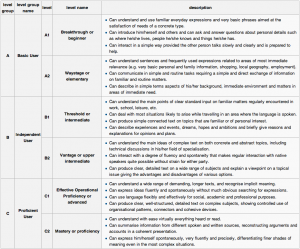

My goal was “social fluency” — the point where I can express myself naturally and fluidly, across a wide range of social situations, and enjoy myself. From my experience and research, this seems to be around a solid B1/B2 level on the Common European Framework scale.

That bar scene in Bariloche was my goal. I didn’t know that it would be in that bar or in that city, but my goal was to have a normal, casual conversation over dinner with friends within eight weeks of landing in Argentina. (That’s a high bar, but I was putting about 4 hours of work in each day on this.) Again, it doesn’t matter what the goal is, but you need to have one.

Perfect ain’t perfect

Nobody is perfect, and nobody speaks perfectly — not even native speakers. Especially native speakers. They aren’t perfect. They’re just real.

One of the hardest things in the beginning of speaking a new language is dealing with feeling self-conscious. I know how it feels — you think through every sentence, afraid of the awkward pause when you don’t know how to say something or the person you’re talking with doesn’t understand you. I’ve been there, and yeah, it’s not that fun.

But without fail, the people I’ve met around the world are helpful and friendly toward non-native speakers making a real effort to communicate. They appreciate and encourage it. Think about the last person you spoke to who was not a native English speaker, but was trying hard — were you judging their English? Or were you happy to help them out and thinking that their English was probably better than your Arabic/Russian/Italian/French/? I’m betting on the latter.

Well, guess what? Same things happens when the roles are reversed. People in other cultures all around the world are not judging you, and are usually delighted to help you out. The fastest way over the self-consciousness hurdle is to look friendly and just start speaking. It will all be okay. I like Benny’s take on this: Just. Start. Speaking.

Avoid English (or your native language)

You can’t translate in your head and speak fluidly at the same time. To get to the point of having interactions at their natural pace, you will have to learn to think in your target language. The good news is that this is much easier than it sounds.

But how?

Simple: don’t translate. Thanks to Gabriel for this idea, one of the language learners / teachers that I most admire.

Gabriel nailed this for me. DO. NOT. TRANSLATE. Doing so is only training you to depend on your native language as a bridge to your target language. What you want is to train yourself to think and communicate in the target language, without the bridge.

A simple example from Spanish: why would you train yourself to think “house,” then “la casa,” when instead you could just see a house and think “la casa”? The latter is much more efficient and effective, if your goal is fluent communication.

Now, what you’ve been waiting for: the approach.

Approach

So, how do I actually learn this? The approach I used is a combination of others, plus a few adaptations of my own. This is where you, dear reader, benefit from my quasi-OCD tendency to research the hell out of topics of personal interest: I spent almost 50 hours consuming and testing different research and approaches, and then distilled those into an approach that combines the best of each. I link to the main approaches I combined in the resources section at the end.

With Spanish I followed the same pattern I use when learning anything new. I begin with two questions: 1. What material is the essential core of this topic? 1. Is there a particular sequence I should learn this material in?

Find the core

Every language shares commonalities because people everywhere are trying to communicate and do the same sorts of things.

Every language has an essential core of words. Learn this core, and you will have a critical building block for all efforts that follow (more on this below).

Sequence

This is the sequence that emerged as I worked on this daily for a few months and helped other travelers with their process. I’ve sequenced it according to where you are in the learning process and according to what level you’d like to reach.

About levels and that oh-so-slippery word, “fluency.” Everyone seems to have their own definition of it. I find it useful to hitch real-world goals, like the “social fluency” I mentioned above, to the European Common Framework for measuring language proficiency. This makes understanding your level easier, more concrete and measurable. The grid below lays out the levels (click for full-size).

If you do nothing else, just follow the steps in the “getting started” sequence and let the rest follow.

Zero to functional (1–5) | Social fluency & advanced levels (6–11)

- Focus on essential material early that will give you a frame to hang new vocabulary and constructs on as you progress. (props to Benny for this).

- Start speaking, immediately. Speak as much as you possibly can in your target language..

- Commit to the sounds and accents. Work on these early, and it will help you later.

- Separate learning and review.

- Practice every day.

- Move to native materials, ASAP.

- Get as much passive exposure as possible.

- Use the principles of the Telenovela method.

- Don’t study grammar until you have a basic grasp of the language.

- Consider hiring a teacher or finding a language buddy

- Force yourself to think in the target language

Zero to functional

1. Essentials, followed by interest

I think of learning any new concept like framing a house: you need to build the frame first, and then you can layer the siding onto that frame. With a language, I believe the initial frame is the most common and essential words in the language (i.e. “the,” “that,” “this,” basic numbers, etc.)

One of they foundational principles in this entire approach is to use English as little as possible and do not translate. But, for these first few hundred words, you’ll have to translate. They are the foundation and frame on which everything else must build. You need some words in a language to acquire the rest, and your native language is your bridge to your first words.

So what are the essentials? We tart with Gabriel Wyner, one of my favorite language learning experts, who provides a good base vocabulary list here here. In addition to his basic list, I would add basic numbers, and then two extremely useful types of phrases: connectors, and “skeleton keys.”

First, the essential words: You’ll just need to learn these cold, because they underly everything. You don’t have to focus on them much after the beginning, because you’ll use them so much they’ll become automatic.

Our second category, connectors, are useful for making your conversations seem more natural earlier on. We all use short connective phrases, which fill in conversational gaps and provide transitions between the things we’re actually trying to say. For example:

- I’m not sure

- what do you think?

- well…

- it’s because

- so…

- although

- but

Learning these basic phrases earlier will help you in 2 ways: 1) makes you seem like a more natural speaker than you are, so people are more likely to talk with you; and 2) it lets you get other people talking by tossing the ball back to them (such as a connective phrase like “I’m not sure; what do you think?”). Shout out to Benny for this idea. Learning some of these common phrases saved my ass when I didn’t know what else to say (read: constantly).

Finally, the “skeleton keys,” as I like to call them. These are commonly used phrases to express the most common intentions: I want, I need, I’d like, etc. In other languages that have verb conjugations (most languages other than English, including all romance languages that I know of), this is a ** hack**: in languages, you can use the intentional phrase + an infinitive (un-conjugated) verb to express tons of ideas. Why is this useful? Because when you’re learning a new language, you have enough going through your head anyway: vocabulary, tone, tense, accent, mood, insecurity, etc. It’s much easier to quickly apply vocabulary you’ve learned in the infinitive form by coupling it with an intentional phrase, than it is to worry about conjugating it. You must learn to conjugate and use verbs as they’re intended, but having a way to express an idea without conjugating turns out to be a useful crutch to have in your back pocket.

Depending on how much time you’re putting into this every day, the above material might take you anywhere from one to four weeks to learn. As you practice, you’ll lock in this foundational material quickly. Following that though, I recommend choosing your material from subjects that you’re personally interested in and would learn about anyway in your native language (my example was cooking; cooking classes and recipes in Spanish kept me engaged when I otherwise would have gotten bored).

2. Start speaking, immediately

This one is self-explanatory. Speak. Speak as much as you possibly can in your target language. Avoid English like the plague.

As a side note, this is one reason that immersion programs or travel to a foreign country can make such a difference in accelerating progress: dramatically reduced opportunities to speak your native language.

3. Commit to the sounds and accents

After a few weeks in Buenos Aires, I was hanging out with my Spanish teacher, Gisela, and we went to a polo tournament, which for the record, was fantastic.

She insisted I try the tramontaña flavor of the famous local ice cream company, and so of course I was dispatched to buy two cones. She followed along just to see what would happen, and proceeded to have a laughing fit as I royally fucked it up. The guy at the counter had no clue what I was saying, and I just kept trying because I was felt determined to pull this off.

Afterwards, when I found Gisela again — with the wrong flavors of ice cream, by the way — she was still laughing. “What’s so funny?,” I asked. And between giggles, she recounted that what was so funny was that I was using all the right words and grammatical structures, but the guy behind the counter still had no idea what the hell I was saying.

The moral of the story? Having the right words and grammar is not enough. If you say them all wrong, it doesn’t matter if your vocabulary and grammar are perfect: no one will understand you, defeating the whole point. It turned out I was making two common mistakes:

First, I was too quiet. Many people whose first instinct is to speak , loudly and slowly when speaking to a non-native English speaker do the exact opposite when the roles are reversed. I certainly did: I was practically meek, which is not a word people would use to describe my usual manner. It’s a strange catch-22: afraid of messing up what I was trying to say, I was too quiet, and therein messed up what I was trying to say.

Second, I was speaking like a gringo. I had a terrible accent that did not at all resemble that of a native Spanish speaker. There are two solutions here: the first, and more important, is to mimic. When you are learning, don’t just mimic the words and structures: mimic the accent of whomever you’re learning from. This means leaning into the sounds, mannerisms, and emphases like a native speaker does. This will feel weird at first because you will not sound like yourself to yourself. Then it will feel fun, because people will suddenly understand you better and will eventually mistake you for a local, which has a host of other travel benefits.

Commit to the sounds and accent from day one. First of all, committing to it from day one means you don’t have to go back and try to change it later. More importantly, it will result in being understood better and in being treated better wherever you go. WIN.

4. Separate learning and review

This is a key point when learning anything, not just languages: don’t try to learn something new and lock it into long-term memory at the same time. New knowledge takes time to be consolidated and transferred to long-term memory, and initial learning is all about getting it locked into short term memory and reviewing at the right intervals so that it efficiently transfers to long-term memory.

Learning

You need to constrain the amount of new material you try to take in. The brain can only take in so much new information in a given day. I recommend learning 15 new words or phrases per day (30 words/day if you’re feeling aggressive).

But how much vocab do I have to learn? Much less than you think.

This study by Mark Davies at BYU investigated word frequency in Spanish to determine how many words were necessary to understand the majority of native material. While this was Spanish-focused, as far as I know the pattern holds true across languages (given that at the general day-to-day level of language, people everywhere are all pretty much saying the same things, just in different languages).

I came across many references to this study while researching methods, so I dug into it. Here are the shocking results, broken out by whether you want to pace yourself or go fast.

Just to drive this home one more time: if you choose your words well and learn 30 per day, you will have enough vocab to understand 95% of the spoken language in 3 months (100 days). That is an amazing ROI on your time. Check out the chart below (and the full study here):

Review

This is where I clue you into one of my secret weapons: Anki. Anki is one of my favorite pieces of software in existence. It is the leading open-source Spaced Repetition Software (SRS) program on the market — free, and cross-platform. What is SRS? Think of flashcards on steroids, but managed by a computer instead of by hand. It’s the most effective tool I’ve found yet for locking information into long-term memory for incredible recall.

If you want to turbocharge your ability to retain new material that you learn (like vocabulary and key phrases), use Anki. Ignore this one at your own peril.

5. Practice every day

Pretty self-explanatory. When you’re learning a new language. you are literally changing how your brain is wired. That takes daily practice and dedication. This needs to just become part of your day if you’re serious about it. Locking in new habits is beyond the scope of this post, but I recommend checking out Beginner’s Mind, on Demand and TinyHabits for more there.

If you do this right, this is an enjoyable part of the day that you’ll look forward to. Especially because you’ll see, feel, and hear yourself improving every single day. And that is motivating.

Achieving social fluency & advanced levels

6. Move to native materials, asap

This is an extension of Do Not Translate. As soon as you possibly can (that is, from day one) use reading and viewing materials that were made for the native audience. In the beginning, this will mean using simple native reading and viewing materials.

Very quickly though, you’ll get bored with the material you’re using. This is normal, don’t worry about it. What do you do instead? Just consume the media you would in your native language, but in your target language. I learned a TON reading stories about cooking and learning recipes in Spanish for some cooking classes I took.

When you use material that you naturally enjoy, it doesn’t feel like work. To me it feels more like unlocking a fun cheat code where you get to do the thing you like and learn this language too.

As soon as possible (once you start to be able to have actual conversations in the target language), you want to get a monolingual dictionary so that you begin to learn new words and phrases using the target language itself.

7. Get as much passive exposure as possible

This is the area where immersion is most useful. By hearing the sounds of the language in the street, in music, on TV, and seeing it written everywhere, you start to pick up nuances (especially pronunciation) that is hard to replicate without this level of exposure.

But what if you can’t travel to a country where your target language is spoken? (time, money, etc). The good news: you don’t even have to, thanks to virtual immersion. Thanks to the web, you can create an environment that gives you most of the benefits of immersion, without leaving home. If you’re going to watch TV, do it in your target language. If you listen to music while working, listen to music in your target language (I, for one, am a fan of the “Intro to Argentine Rock” Rdio playlist). You can find great radio from around the world on the web at TuneIn, the BBC, or on YouTube.

This is where I want to give a shoutout to…

8. Use the “Telenovela Method”

“The Telenovela Method” is a clever and fun way to learn a lot of your target language. (The resource lists he includes in that book are worth the price of purchase on their own.)

The gist of the Telenovela method is to use material (TV shows, movies, books) that was created for a native audience, and to work your way through them slowly. Scene-by-scene or sentence-by-sentence, learn everything you need to fully understand the material. Add it to Anki once you truly understand it. Rinse & repeat.

This, on its own, is a powerful way to build your vocabulary and grammatical skills and to pick up the intonations and vocal mannerisms of a native speaker. But I recommend it as an augmentation of the other, more conversation-based techniques I’m outlining here. If you only have time for one, choose those, as it will get you actually speaking in and using the language, which is the actual point anyway (not much use if you don’t use it…).

9. Don’t study grammar until you have a grasp of the language

Starting with grammar is akin to the idea that if you memorize enough rules of a game, you’ll know how to play it. Just because I know the rules of football, or cricket, or swimming, does not mean I am any good at those skills. Why would the skill of language be any different? (Remember: it is just a skill, and therefore learnable and trainable like any other.)

You will need an excellent grammar book and to spend time internalizing this part of the language. But grammar is boring as hell until you actually have personal experience in the language to use it on. Once you’ve been using and speaking the language every day for a few weeks and are underway, THEN you can return to grammar. With this basis, it will actually help you understand what you’ve already seen as opposed to confusing you with a bunch of rules that seem arbitrary and out of context.

10. Consider hiring a teacher or finding a language buddy

Having another person there who knows the language can be immensely helpful, especially as you progress to a more nuanced level. This can cost as little as $5/hour on iTalki or it can be free with a language exchange buddy. Effort determines outcomes here.

11. Force yourself to think in the target language

This one is self-explanatory: as you’re walking around during the day, trying to think in your target language.

Start simply: when you see a dog, think the word for “dog” in your target language (without translating). Keep doing this and gradually you will build up the mental muscle and practice of thinking directly in your target language without translating.

Learning a new language doesn’t need to be scary, or expensive, or this all-consuming thing that takes over your life (although that can be fun, too).

Combine the highest-frequency material with a good learning approach, use it every day, and retain what you have learned. I share a ton of resource links in the FAQ below — if I’ve missed something good, let me know and I’ll add it.

There’s a big, wide, happy world waiting for you to come out and unlock new cultural and travel experiences. This can be your key.

Good luck! I hope you’ve found this useful. Please leave a comment below and let me know how this works for you, what works, what doesn’t, and any questions you have.

FAQ

Where can I download Anki decks?

The truth is, you will have much better experience and enjoy better performance if you make your own cards. There are several reasons for this: 1. Anki is a phenomenal tool for retaining what you’ve learned, but not for initially learning something. There is an initial foundation of understanding and retention that occurs when you actually learn something on your own. You skip this if you get your cards “off the shelf.” Also keep in mind:

- Having to catch up on tons of cards can quickly get overwhelming and take a lot of time. If you’re aggressively using downloaded decks, you may soon find yourself in a position like me where I missed 2 days and came back to having to review almost 1,000 flashcards for Spanish alone in one morning review session. Not so fun.

- Other people are often not as careful as you in creating / maintaining their decks. I have memorized things that were wrong because I was using someone else’s deck.

- If the image on your card is at all ambiguous (which will happen often), you may not remember what it was actually supposed to mean, since you didn’t make the card. This leads to false positive/negatives, which messes up the review patterns and schedule determined by the Anki algorithm.

That said, I totally get it if you want to download one of the many decks on a specific topic that are available online here. You can also download my personal, hand-crafted Spanish deck (with images and media) here.

I’ll quote Gabriel’s advice on learning from a downloaded deck, which I think is spot-on:

…that being said, if you’re dead set against making your own deck because you have no hands or something, you can make using someone else’s deck more effective by splitting the memorization and learning steps…

Download the deck, install it, and suspend every single card. Go through the suspended cards and choose the ones that are clear in meaning to you. Use a dictionary to make sure they mean what you think they mean. Un-suspend those cards and learn them over a week or so. Now go back and un-suspend more cards. Keep doing this, and you’ll eventually learn all the concepts, and then be able to use Anki to effectively memorize them.

How should I make Anki cards?

Generally, follow Gabriel’s advice here. The key points are:

- Use images for anything possible.

- If a word is at all ambiguous, use two images. This way it’ll be clear during review what you’re looking at.)

- Use definite articles (example: “la ala”, not just “ala” for “wing”). This is very important if definite articles are less common in your native language than in your target language, (such as English vs Spanish / most romance languages).

- Simple is better.

What random tricks helped?

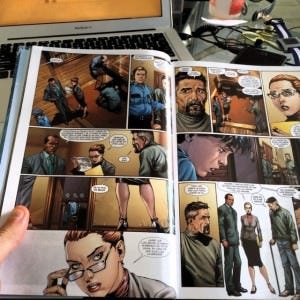

Reading comic books. They’re written for a native, casual audience, and they are almost 100% dialogue. Comic books do a great job capturing the way the language is actually used by real people in their everyday lives. Plus, they have awesome art and cool stories.

If comic books aren’t your thing, any relatively dialogue-heavy text will do, like a children’s book (especially if you can get a parallel text in your native language when you can’t understand something). “The Little Prince” was and is a favorite of mine, now in two languages.

Using Google Images as a foreign language dictionary works well, especially once you adapt to the “don’t translate” principle.

Make a one-page self bio in the target language and go through it with a native speaker to improve it, make it fluid, and learn how to pronounce it right. Once you’ve got it, practice and memorize it, and voila! you’ve basically memorized / scripted your answers to the first 5 minutes of meeting anyone new, and done so in a way that will make you sound more native and make them more likely to respond positively to you. Winning.

How do you structure a good language exchange with a conversation partner?

This is an art unto itself, and I think the reigning master is Andrew Tracey (he covers this and lots of other great resources in his book).

That said, you want to keep it interesting and engaging for both you and your partner. You’ll want to switch back and forth between languages, say every 15–20 minutes.

If you want to go the conversational route, here is a list of good conversation starters that I’ve compiled, ranging from lighthearted to heavyweight topics. Further, here are other tips I’ve compiled from various resources about how to structure a good exchange.

How do I retain what I’ve learned?

Frankly, I wouldn’t worry all that much about retention for now. If you’re actually using the language & Anki every day (which you should be) then you’ll already be retaining a lot of what you know. And the rest of the language you have learned isn’t gone, it’s just hibernating. I like Tim’s recommendations for reactivating a hibernating language here.

Where do I go for more?

Here’s a compiled list of resources that I used all the time.

Online tools & communities

- Lang-8: native speakers correct your writing in the target language

- Forvo: get native pronunciations of almost any word. Amazing when you just don’t know how to say a word.

- Google image search in your target language (Spanish here): when I don’t know a word in my target language, this is my first stop.

- Anki

- FluentLi: good for getting usage questions answers, like “how would you actually use this phrase in day to day life?”

- Verbling & LiveMocha: both offer live, drop in video classes in foreign language. I didn’t do much of these, but they caught my eye.

- How to Learn Any Language: good forum if you want to nerd out on language learning.

- Here’s a spreadsheet for Spanish that you can use to build out your decks / Anki cards (Google how to do it by importing a CSV to Anki). It includes the first 400–500 words, many useful / common connector phrases, and then the highest frequency 2,000 words in the spoken language.

- Spanish Google Images search (preset to good image sizes for Anki)

- Spanish Google Images search, preset to show captions below the images. This way, you always have native text to use in Anki with the image.

- About.com Spanish reference. Actually quite good at explaining many confusing concepts.

iPhone Apps

In addition to being good at their primary task, these apps work offline. This is a lifesaver when traveling. I link to Android equivalents where I know them — if you know something I’ve missed, let me know in the comments and I’ll add it.

- ConjuVerb (free): offline Spanish verb conjugation. After you use it for awhile, use the built-in flashcards tool and lookup frequency lists to add to your Anki deck. This Android app looks like an equivalent but I haven’t tested it.

- SpanishDict (free): great Spanish dictionary. Also has a good online presence. Android version here.

- Anki ($25): Anki, on your iPhone. Absolutely worth every penny. No question. Free Android equivalent here.

Books

- Fluent Forever, by Gabriel Wyner

- The Telenovela Method, by Andrew Tracey

- In Other Words, by Kenji Hakuta

- Fluent in 3 Months, by Benny Lewis

Blogs/Forums

I want to send lots of thanks to Benny Lewis, Tim Ferriss, Andrew Tracey, and especially to Gabriel Wyner. Their work formed the core of the approach that helped me immensely and unlocked a whole new way to see the world for me.

I am deeply grateful and recommend you check out / subscribe to their blogs if this is an area of interest for you.

If you really want to nerd out, I also recommend checking out the How To Learn Any Language forum.

What didn’t work?

- Focusing on grammar first, or even early

- Writing to use the language without getting it corrected. Use Lang-8 for this; write short, fun entries using whatever words or phrases you’re focusing on or struggling with. You’ll remember them better and get corrections on how to use them, all in one go!

- Trying to write or read about something I wasn’t fundamentally interested in (like some boring historical event); to stay engaged, I needed material that appealed to my interests

- not using definite articles in Anki: in English, we don’t use definite articles (“the”) anywhere near as much as other languages do.

- Translating: this is the big trap that I and damn near everybody I know has fallen into. Translating is slow, tiring, and boring for your conversational partner. Moreover, your goal is NOT to train yourself to translate. Your goal is to train yourself to communicate fluidly in this new language. After those initial 300–400 base vocab words, translation is only slowing you down and making you dependent on a crutch you don’t need.

What if I’m just going on a quick trip somewhere, and don’t want to learn the whole language?

Fair enough. You’re going on vacation for two weeks — worth bothering to learn anything? I’d say so. There is immense value in getting the basic words and phrases (i.e. the initial 400).

Without fail, putting forth an honest attempt to speak in the local language will get you treated better than the opposite. You’ll get better deals, more sympathy, more help, and maybe some amazing new cultural experiences that locals invite you to join in.

So, yes, at least learn something. A little bit of effort here can have an outsized impact on the quality and fun of your trip.

What are the flaws with this approach?

You’ll quickly become more interesting and attractive, so your social calendar may get quite full. Don’t come whining to me when you’re too busy doing awesome new stuff.

But in all seriousness, I can think of two things about this approach that you may consider a flaw, depending on your personal goal:

- I heavily prioritize spoken language over written language.

- I don’t know how this process would need to change to get to a true level of mastery with a given language. This approach is aimed at getting to social fluency and general fluency, not aimed at the level of being able to give a 30 minute highly technical testimony in front of Congress in the language.

How much will this cost me?

This process can work on its own, for free and without paying for any classes. Many of the best resources are free (I listed them above). That said, your progress may speed up if you find a good teacher to help you with more advanced grammar and linguistic nuance after you already have a solid, working handle on the language.

Which language should I learn?

Whichever you actually feel motivated to and interested in. Whether you want to learn a language to surprise a loved one, unlock new career opportunities, or just because you like the sound of it — all these are perfectly good reasons.

That said, when choosing a language you will want to:

- Consider the sounds: if your target language has sounds that do not exist in your native language, it is going to be harder. There are tongue and throat muscles and patterns that you just don’t have right now.

- Deconstruct the language with the help of a native (or Google) to see how different its structure is from your native language. Is the word order different? Do modifiers go before or after that which they modify?

- Consider the language difficulty charts. The US Foreign Service Institute and Defense Language Institute chart out languages based on Category 1–4, with each step up in number representing the expectation that it will take twice as long as a language at the level below it.